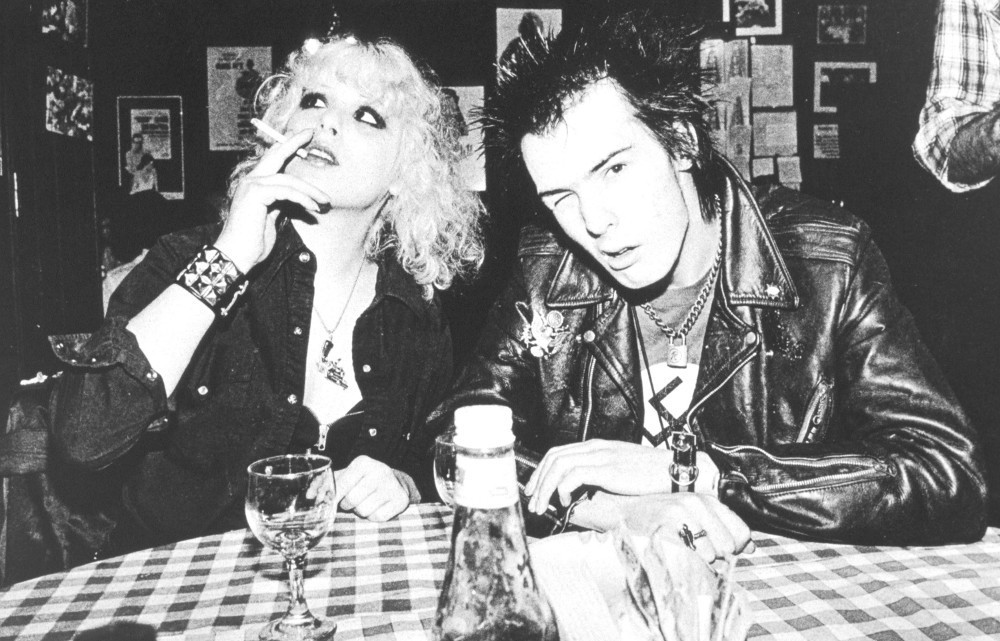

Two years doesn’t really seem like a long time, unless you’re given two years in jail, which would probably seem like an eternity. Other than that, two years is pretty much nothing. If you live in NYC, two years is probably your lease, and at the end of it, your landlord raises your rent an unfathomable amount and it’s time to move. So two years is more like, “Oh yeah, when I lived in Greenpoint? Shit, I forgot I even lived there.” On the other hand, a lot of shit can happen in two years. For example: Sid Vicious went from: unknown, to bassist of The Sex Pistols, to rich and famous, to accused murderer, to dead, in two years. I once dated a girl for two years and if I bumped into her in the street today, I probably wouldn’t recognize her. Sid died 35 years ago and not only is he still talked about, we still recognize his face and listen to his music. We all know the story: Sid moved to NYC into the (in)famous Chelsea Hotel with his girlfriend Nancy after the Sex Pistols broke up. There they took to being full-time junkies, with plenty of cash to do it. Eventually, we are told, Sid Stabbed his love Nancy in the abdomen, killing her, and so began the tale of punk rock’s Romeo and Juliet.

Did Sid kill her? Did she kill herself? Did she fall on the knife? Did they have a suicide pact? Did some dealer do it? We probably won’t ever know. Actually that’s bullshit, we’ll probably have a time machine eventually and just go back and take a peak. Until then, it’s really just conjecture, but it’s fun to talk about. Unsolved mysteries are interesting, especially with famous people. Double when the famous people in question are remotely interesting. So I met with a psychiatrist who met with Sid shortly before his untimely death, to talk about his experience with the now legendary Sid Vicious.

Dr. Stephen Teich Photo by Timothy White

So what area of psychiatry do you work in?

Well, I primarily do Forensic Psychiatry. As a general psychiatrist I’ve done some treatment but I have been working in the forensic field since 1972. I even did some things before that during the war (Vietnam), like evaluations of people who had issues they were raising with the military and law enforcement. That’s all it is, doing regular psychiatric evaluations in the context of the legal issues that are being contested in the court.

Where were you working in 1978?

I was doing private independent work by that time. I didn’t work for or in any particular place after 1975.

How did you wind up working with Sid Vicious?

By his lawyer. He wanted me to do an evaluation for him. Actually, he was worried about him at the time because he was talking suicide and he wanted to see what went on. The result of it is we had him hospitalized because he was not controllable by his family.

Were you familiar with him or his band before his lawyer contacted you?

Not particularly. I mean I knew of him but nothing particular.

Do you remember how long it had been since the murder of his girlfriend when you saw him?

A number of months.

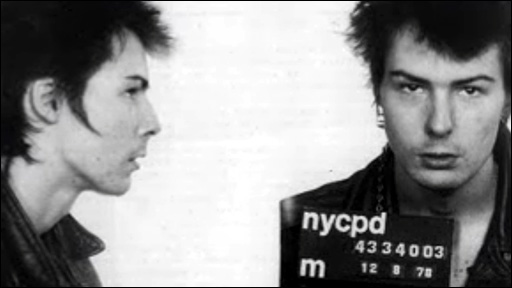

He was released initially after the murder but arrested again after getting into a bar fight. Was that around the time you saw him?

It was after that. He was out again. You know we had him taken into Bellevue and I think he was then transferred up to New York Hospital in Westchester for a while. Then they released him and I think it was shortly after that that he actually killed himself.

When you saw him the first time, he was only 21 years old — did that immediately make an impression on you? That this was a kid, basically?

Well, we had talked about what was going on. What was clear was that he was very young and he had gone through some extraordinary experiences because of the phenomena of the band and where they were, and something had been very impactful on him. I remember that he had talked about going to East Germany, to East Berlin, and was struck by the nature of the working class and what was going on there because he came from the working class and had a lot of feelings about that. My time seeing him was really an evaluation for his suicidality at the time.

I saw him in his hotel room and then I got a call later because I had told the family that they shouldn’t leave him alone and always be with him and so forth, and so they actually left him alone and he slashed his arm and they called me back over and I was talking with him and decided that we had to call EMS to have him taken to the hospital. Because the family wasn’t going to give the kind of care that was necessary. When he saw the police at the door with EMS he tried to jump out the window so I grabbed him.

How far did he get out the window?

No, he was just in front of it.

Were the police in touch with you at any point?

No, no. I talked briefly with his lawyers but then he changed lawyers and I had no further contact.

He was only famous for about two years and he did come from a poor neighborhood, raised by a single mother. Did he say anything else about his experience in East Berlin?

That’s all I really remember. We were trying to talk with the television on because he didn’t want to turn the television off, and he didn’t really want to talk to me, so it was a sort of distracted talk.

Was he sober when you spoke to him?

Fully sober? Probably not. Was he reasonably coherent? Yeah. You could make contact with him and talk to him.

Did he strike you as an intelligent person?

Yeah, actually.

Could you tell that he was still in love with his now dead girlfriend?

Well, there’s no doubt that that was an emotionally overwhelming event. I think he felt some guilt for it, whether he had any or not. You know, love at that age is a combination of things lacking from the past and all sorts of things. So it’s a whole different ballgame that you’re playing with, you’re playing with love: Psychological, internal psychological and your unconscious psychological issues that are not going to change, have not been satisfied. Maybe there had been negatives, maybe magnified by whatever happens. But I didn’t have enough time to really evaluate all that.

Did you want to see him again or was it really just up to his lawyer?

It was up to his lawyer, but the plan was, I was gonna see him the next day. You know, do a follow up, check on him and see how he was doing. But later that afternoon he cut his arm, I was called back over and we put him in the hospital.

That was the last time you spoke to him.

Yeah, that was the last time I saw him.

So were you surprised when you heard that he had overdosed, killing himself?

No, I wasn’t surprised because the kind of depth of treatment you often get in a hospital is more superficial and often, simply medication, and that wasn’t what was going on with him. He had a lot deeper things. What I told you about East Berlin and his views, is that he had become essentially political, it had stirred him up politically at a level of looking at society. That wasn’t a minor thing for him because of his upbringing.

Did you get a sense that he was shunning his wealth and fame?

It wasn’t, I think the wealth what was it was but I think the fame was a little bit oppressive. There were too many demands on him that he didn’t know how to deal with. He just wanted — at this point — with the loss of his girlfriend, he wanted some space to himself. He didn’t want to be out there. You know he couldn’t put on what you needed to be out there at the end of it, he was dealing with internal things.

Did you ever speak to his mother or any people close to him?

I think I spoke to his mother briefly and a couple of times on the phone but I never really went into history with her. It was more about dealing with what was going on in the present or I think at one point I talked to her after he died, just to follow up with her.

Is there anything else you remember from seeing him?

You know his manager was around.

Was that Malcolm McLaren?

Yeah, probably as with all managers it was a mixture of what was going on. Part of it was the business of it and part of it was personal I think. In some ways he was running things, which wouldn’t be surprising because that’s what he does. He wasn’t terrible happy that we put him in the hospital. Image-wise. But he was OK with it and I don’t know what role he played afterwards.

Dr. Stephen Teich is a graduate of Princeton University and has been working as a psychiatrist In New York City for over 40 years.

Interview by Timothy White. Follow him on Twitter @TipToTheHip